Viking Textile Tools: Spindles

Drop spindles were ubiquitous until the invention of the spinning wheel and subsequent industrialization of the yarn production process. Andersson (2003) makes some estimates of the amount of yarn needed for clothing at Birka. Scaling her figures down, to make one set of garments for an adult couple required:

- 6 kg of raw wool, the product of 3-6 sheep

- 36,300 m of yarn (assuming 12 threads/cm for twill, 6,050 m/kg for mixed wool (hair and wool, characteristic of early sheep breeds)

It is difficult to estimate the time needed to spin, weave and sew this clothing because little is known about who and how many people would have worked on it, but it definitely would have taken a long time, and spinning the yarn was by far the slowest step.

Spindle whorls

The usual drop spindle consists of two parts, the whorl and the shaft. The whorl weights the shaft and improves its spinning characteristics, while the shaft makes it easier to handle and provides a place to wind the finished yarn. Both under- and over-weighted spindles were used in Viking Scandinavia (Andersson 2003). The weight and diameter of the whorl impact the rate and duration of spin of the spindle, which affects the character of the finished yarn. The weight of the spindle also affects the yarn produced because it determines the tension on the wool fibers. Small spindles are used for thin threads because they rotate faster, and heavy spindles are used for plying yarn (Woodland 1990, Andersson 2003). The average household would have possessed a variety of spindle whorls suitable for producing the types of yarn needed for clothing and household textiles. Because of this, there are no temporal trends in spindle size or shape - all were common throughout (Andersson 1998). In Viking-era Scandinavia, whorls were made from various dense materials, including bone, antler, wood, amber and soft types of stone.

Soapstone spindle whorls were most common in Norway and western Sweden, where soapstone was readily accessible (Mortensen 1998, Roesdahl and Wilson 1992). Spindle manufacture in early Scandinavia and England seems to have been a domestic process, with whorls and shafts produced as required by the spinners from available local materials (Walton Rogers 2000). Although half of the 429 whorls found in the Birka area were of stone, only 2 were definitely soapstone, and were probably imported from Norway (Andersson 2003). There were definite differences in shape among whorls of different materials. Stone whorls were usually discoid or flat-convex, while conical and biconical whorls were usually ceramic. Conical stone whorls have been found, but they are rare. The whorls from Birka ranged from 4-100 g, with most falling in the 5-29 g range (Andersson 1998, 2003). Stone whorls tended to be heavier, in the 10-40 g range. The diameters of whorls of all types ranged from 25-45 mm. Whorls of this diameter are common because they spin well; stone whorls tend to be heavier because of the greater density of stone. The height of stone whorls is 5-20 mm, with a 7-12 mm hole. Stone whorls tend to have larger holes than those in other materials.

The spindle whorls from Hedeby were mostly ceramic; of the 939 whorls found, only 33 were of stone (Andersson 2003). Standardization of the size and shape of the ceramic whorls suggests that these were being mass-produced. The stone whorls were flat or flat-convex, as at Birka, and the sizes were similar. Stone spindle whorls could have been lathe-turned, carved with a knife, or shaped with a rasp, further supporting the idea that most were produced within the household as needed, using minimal tools. Of the 92 stone spindle whorls found in Anglo-Scandinavian York, only about a quarter were lathe-turned (Walton Rogers 2000).

Spindle shafts

Almost no spindle shafts were found at Birka, but at Hedeby, where organics were more likely to be preserved, 36 wooden spindle shafts were found from Viking contexts (Andersson 2003). They ranged from 98-215 mm in length, with diameters from 5-13 mm. Shafts with a 7-8 mm diameter were most common. Wooden shafts always are thickest in the middle and tapered to both ends. Yew was the most common wood, but spruce, beech and elm were also represented Reconstructions in yew weighted 2.5-7.5 g. About a third of the shafts from Hedeby show wear 35-45 mm from the end, where the whorl sat.

A large collection of spindle shafts, over 800, was found at Novgorod, in layers dated to the mid-10th c. and later (Kolchin 1989). These were larger than those from Hedeby, usually 250-300 mm in length and with a diameter of 12-144 mm. Over 20 of these spindles still had wool on them. Some of the spindle shafts were turned on a lathe; these were commonly decorated with circular lines. Others were carved, and are usually undecorated.

Materials

I chose to make these spindle whorls from soapstone (steatite), a dense but easily worked material. Soapstone was commonly used in Viking Scandinavia for a variety of household items, including pots and lamps. Soapstone is primarily composed of talc, but may contain other minerals that affect its hardness and color. The soapstone I used is from South Carolina; I was unable to find detailed comparisons of soapstone from different regions, so I cannot evaluate differences between this soapstone and that used in Scandinavia. The use of soapstone was considerably less common in eastern Scandinavia than it was in Norway and western Sweden because of the lack of local quarries. I chose to use it anyway because of its availability and ease of working. The wealthy Viking woman who would possess this set of tools could have afforded imported spindle whorls, and there were a few of them found at Birka.

The shafts were cut from hardwood saplings of species commonly found in southern Pennsylvania. Black cherry (Prunus serotina) and striped maple (Acer pennsylvanicum) were reasonably straight and of the proper diameter. These species are North American, but other species in the same genera are native to Sweden. All of the extant shafts are tapered to both ends, with the widest point just above the shaft.

Tools and Techniques

Stone spindle whorls ranged from crude disks cut from broken pots to finely finished and decorated whorls of various shapes. Some appear to have been hand-carved into roughly circular forms, while others were obviously turned on a lathe. Many of the latter have incised decoration. Iron saws and files are known from Viking Scandinavia (Roesdahl and Wilson 1992). While these examples come from a set of blacksmith’s tools, similar items could have been used to shape stone. I used modern versions of period tools, a hacksaw and files, to shape the spindle whorls.

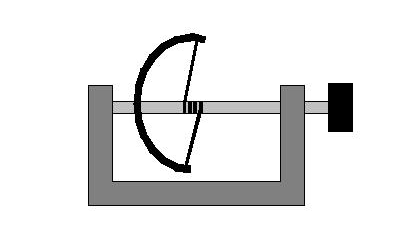

Because I was trying to replicate the tools used by an upper-class woman, I decided to make nicely-finished lathe-turned whorls. I built a crude bow lathe to turn the whorls on (Fig. 1). Pole lathes are well-documented, but not really appropriate for turning small round items like jet and amber beads, or spindle whorls. A smaller bow-driven lathe would be more useful for this purpose (MacGregor 1976, MacGregor 1985). A similar tool, probably a disk-cutter, is pictured in the Mendelschen housebook, and was my source of inspiration for this tool (Egan and Pritchard 1991) My version is much simpler, and clamps to a workbench. Although I did build an end stock with dead center, I found it easier to mount the stone block to the shaft and work it without the endstock. I used wood glue to mount the stone because it held long enough to drill and shape the whorl, but could be released easily. Although I cannot document it, pitch or a similar substance could have been used to mount small round or discoidal objects to a lathe shaft. Panter (2000) discusses in detail the possible methods for attaching small pieces of amber to a spindle stock, but the lack of evidence makes it very difficult to determine how most pieces were done. The decoration on the incised whorls was cut in with an awl while the stone was turned in the lathe.

Figure 1. A simple bow lathe. The support (dark gray) is clamped to a bench. The shaft (light gray, a 3/4 in dowel) rotates freely in the right support, and is held by a depression in the left support. A soapstone block (black) is mounted to the shaft with glue.

I finished the spindle whorls to a smooth surface with modern sandpaper. Not all stone whorls were finely finished, but I prefer to use tools that are pleasant to handle. It is difficult to document smoothing and polishing techniques to such an early date, although the condition of some stone, bone, metal and wood items demonstrates that such techniques were known. MacGregor (1985) discusses methods that were probably used on bone implements. Initial shaping and smoothing would have been done with files and knives, and pumice was used to smooth bone and wood. “Sandpaper” made from dipping leather into fine sea sand may have been used. MacGregor also suggests that horsetail (Equisetum) stems or coarse fishskin might have been used for polishing. Equisetum arvense is native to AEthelmearc, but is not available in the winter. These methods could also be used to polish soft stone.

The shafts were whittled down to the appropriate size using a small knife, then lightly smoothed with sandpaper. The ridges on a whittled shaft will help prevent the yarn from sliding around the shaft during spinning. Both spindles and shafts were finished with walnut oil; constant exposure to wool would produce much the same effect, but I didn’t have any lanolin on hand.

I drilled a small pilot hole while the whorl was mounted on the lathe, and filed it out to fit the shaft after the whorl was finished. It was very easy to split the whorl while enlarging the hole and fitting the shaft, especially if there were any flaws in the stone. I included one of the split (and reglued) whorls here because I otherwise like the way it turned out.

Discussion

The disk-shaped spindle whorls are 14 and 36 g, the incised cone is 27 g, and the plain cone is 36 g, all within the range of weights found at Birka. The shafts range from 2-6 g, again consistent with the historical material. My bow lathe worked very well, for such a simple contraption, and I had a lot of fun shaping and polishing the whorls. Cracking them while fitting the shafts was considerably less fun.

My initial experiments suggest that the discoidal whorls spin much better than the conical whorls - the larger diameter helps to prolong the duration of spin. The somewhat-irregular shafts wobble a bit, but don’t seem to affect the results much. I tried to carve them from straight saplings, but even the straightest saplings aren’t really. Whittling them down farther from a larger piece of wood might be a way to get a straighter shaft without lathe-turning it.

Now that I have spindle whorls in a range of sizes, I am equipped to produce both light and heavy wool or flax yarn to clothe my family and provide household textiles.

return to the project page

References

-

Andersson, Eva. 1998. Textile production in late Iron Age Scania - a methodological approach. NESAT 6, Göteborg University Department of Archaeology.

-

Andersson, Eva. 2003. Tools for Textile Production from Birka and Hedeby. Birka Studies 8. Excavations in the Black Earth 1990-1995. Stockholm.

-

Kolchin, B.A. 1989. Wooden Artefacts from Medieval Novgorod. BAR International Series 495(i), USSR.

-

MacGregor, Arthur. 1976. Anglo-Scandinavian Finds from Lloyds Bank, Pavement, and Other Sites. The Archaeology of York: The Small Finds 17/3. York Archaeological Trust.

-

MacGregor, Arthur. 1985. Bone, antler, ivory and horn: The technology of skeletal materials since the Roman period. Croom Helm, London.

-

Mainman, A.J. and N.S.H. Rogers. 2000. Craft Industry and Everyday Life: Finds from Anglo-Scandinavian York. Vol 17: The Small Finds, Fasc. 14. York Archaeological Trust.

-

Mortensen, Mona, 1998. “When they speed the shuttle” The role of textile production in Viking Age society, as reflected in a pit house from Western Norway. NESAT 6, Goteborg University Department of Archaeology.

-

Panter, I. 2000. Amber working tools and techniques. Pp. 2501-2519 in: A.J. Mainman and N.S.H. Rogers. Craft Industry and Everyday Life: Finds from Anglo-Scandinavian York. Vol 17: The Small Finds, Fasc. 14. York Archaeological Trust.

-

Roesdahl, Else, and David M. Wilson. 1992. From Viking to Crusader: The Scandinavians and Europe 800-1200. Rizzoli, New York.

-

Walton Rogers, P. 2000. Stone spindle whorls. Pp. 2530-2533 in: A.J. Mainman and N.S.H. Rogers. Craft Industry and Everyday Life: Finds from Anglo-Scandinavian York. Vol 17: The Small Finds, Fasc. 14. York Archaeological Trust.

-

Woodland, Margery. 1990. Spindle-whorls. Pp 216-225 in: Biddle, Martin. Object and Economy in Medieval Winchester. Oxford University Press.